I. Historical Background and Creative Context

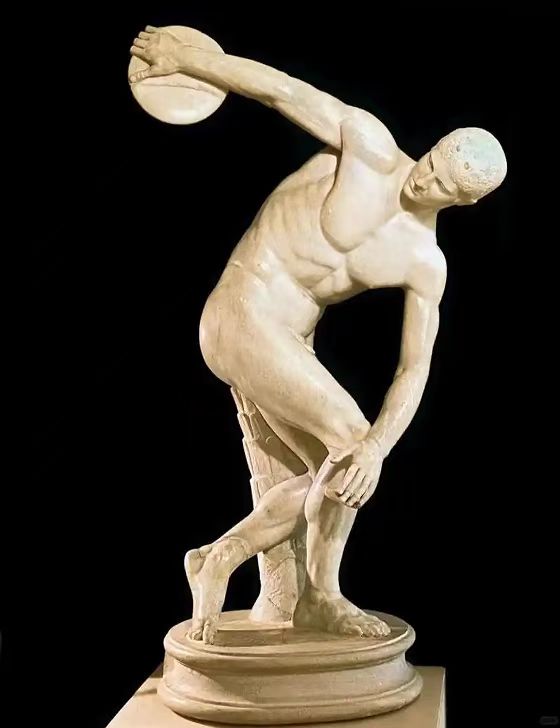

Myron of Eleutherae was active in the mid-5th century BC (about 480-440 BC) and was one of the most innovative sculptors in the early classical period of ancient Greece. Although the original of his masterpiece “Discobolus” (Discobolus) has been lost (presumably cast in bronze), it has been circulated through marble copies of the Roman period (such as the Lancellotti version and the Massimo version), becoming a milestone in the expression of human dynamics in ancient Greek art. This period coincided with the prosperity of Greek city-states and the prevalence of the Olympic spirit. The worship of competitive sports and human beauty was elevated to a sacred height, and sculpture became a concrete carrier of rationality (logos) and harmony (harmonia).

- Formal Analysis: Dynamic Balance and Anatomical Rationality

- The Revolutionary Nature of Spiral Composition

Miron broke through the rigid symmetry of Archaic Period sculptures (such as the Kouros statue) and reconstructed the human body space with “spiral dynamics” (contrapposto spirale). The body of the discus thrower twists in an S shape: the right arm is pulled back to the limit, the left arm touches the right knee, the trunk muscles are tense in the direction of the force, and the face remains detached and calm. This “dialectic of movement and stillness” embodies the “noble simplicity” of ancient Greece (Winckelmann’s words) – solidifying the instantaneous explosive power into eternal order. - Anatomical idealization

Despite the intense movements, Myron’s treatment of human proportions strictly follows classical norms:

- The head-to-body ratio is 1:7, in line with Polykleitos’s “Canon”;

- The muscle lines are clearly discernible under the tension of movement, but not exaggerated (different from the Hellenistic “Laocoon”);

- The center of gravity of the foot falls on the right leg, and the left toe touches the ground lightly, forming a physical and visual balance.

- Missing “gaze” and spirituality

Unlike later Renaissance sculptures, the discus thrower’s facial expression is calm and restrained, and his eyes are focused on the discus in his hand rather than the audience. This “introversion” echoes the pre-Socratic Greek philosophy that beauty is the manifestation of mathematical harmony, not the expression of individual emotions.

III. Cultural metaphor: competition, divinity and city-state ethics

- The embodiment of the Olympic spirit

Discus throwing is the core event of the ancient Greek pentathlon, symbolizing the perfect combination of strength, skill and wisdom. Myron shaped the athlete into a “heroic” citizen model. His body is not only an anatomical masterpiece, but also the embodiment of city-state ethics (aretē, excellence) – pursuing the immortality of divinity through competition. - Geometry and cosmology

The dynamic arc of the work implies the geometric interweaving of circle (discus), triangle (torso) and spiral (motion trajectory), which coincides with the Pythagorean school’s idea that “everything is number”. The moment when the discus is about to be released is both the apex of physical movement and the suspension of time – suggesting that humans touch eternity through reason (nous).

IV. Reception and reconstruction in the history of Western art

- Rediscovery of the Renaissance

After the Roman replica of the Discus Thrower was unearthed in the 15th century, its dynamic composition profoundly influenced Donatello and Michelangelo. The latter borrowed the technique of center of gravity transfer in David, but broke through the classical restraint with a more dramatic confrontation posture. - Paradigmization of Neoclassicism

In the 18th century, Winckelmann regarded the Discus Thrower as a typical example of “quiet greatness” (edle Einfalt, stille Größe), which became the visual sustenance of rationalism in the Age of Enlightenment. Antonio Canova’s Perseus continued this idealized human aesthetics. - Deconstruction of Modernism

Rodin retained his focus on muscle tension in The Age of Bronze, but dispelled classical certainty with vague momentum; Futurism (such as Boccioni’s The Unique Form of Continuity in Space) further shattered Myron’s “moment” into a phantom of movement in the mechanical age.

V. Controversy and Critical Perspectives

Some scholars (such as J.J. Pollitt) pointed out that the Roman replica may have simplified the complex bronze casting technology of the original, resulting in the softening of muscle lines; other studies believe that ancient Greek athletes actually threw the discus in an upright position, and Myron’s exaggerated twist was more out of aesthetic considerations. This treatment of “artistic truth is higher than reality” precisely highlights the essence of “mimesis” in the classical period – not copying nature, but refining its inner perfection.

Conclusion: Dynamic Eternity

“The Discus Thrower” transcends the reproduction of the competitive scene and becomes the ultimate metaphor of ancient Greek “humanism” – in the tension between reason and passion, moment and eternity, individual and universe, the human form is sublimated into the scale of divinity. As Heidegger said, Greek art is “the truth of beings placed in the work by themselves”, and Myron’s discus still draws an unfinished arc in the void.